A team of researchers from the University of Saskatchewan (USask) has successfully developed a three-dimensional bioprinted lung model that could revolutionize how scientists study, diagnose, and treat chronic and infectious lung conditions such as tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, and viral respiratory diseases. The innovation bridges the gap between traditional laboratory techniques and real human physiology — a step that could lead to faster, more accurate breakthroughs in respiratory medicine.

The project, led by scientists from the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) in partnership with the College of Engineering, focuses on overcoming the limitations of current research models. Conventional two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures and animal-based studies cannot fully replicate the complex structure and mechanical behavior of human lungs. The new 3D system addresses this issue by incorporating biological scaffolding and living cells to emulate how lung tissues grow, breathe, and respond to infection.

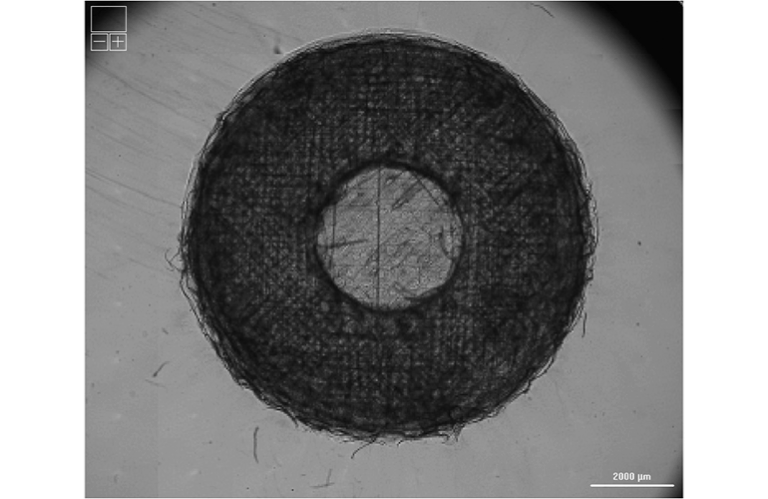

At the core of this breakthrough is the use of the extracellular matrix (ECM) — a natural structural network that supports and organizes cells in the body. To recreate this environment in the lab, the USask team produced bioinks made from decellularized lung ECM blended with living human lung cells. Using advanced 3D bioprinting technology, these bioinks were layered into intricate patterns that mirror the porosity and elasticity of real lung tissue.

Researchers at VIDO provided the biological materials and cell cultures, while engineers at the College of Engineering developed and optimized the printing process. To confirm the precision and quality of their models, the group utilized the Canadian Light Source (CLS) synchrotron, a state-of-the-art facility housed at USask. This imaging technology allowed the scientists to examine the printed tissues in extreme detail — without damaging or altering the delicate samples — confirming that the scaffolds maintained the necessary shape and structure to support healthy cell growth.

The initial findings showed that human lung cells remained viable and proliferated within the 3D matrix, forming tissue structures that behave more like actual lung tissue compared to flat cultures. These results indicate that the model can serve as a realistic testing platform for studying how infections spread in lung tissue, how drugs penetrate the respiratory membrane, and how the immune system responds to pathogens.

“Until now, we’ve lacked a realistic, human-based model for studying lung disease,” explained Dr. Nuraina Dahlan, a VIDO scientist and one of the study’s lead researchers. “Without that, it’s been very difficult to design effective therapies or predict how patients might respond to treatments. This technology gives us a much closer representation of what actually happens inside the lungs.”

The implications for public health and biomedical research are significant. Diseases such as tuberculosis continue to cause widespread morbidity and mortality, in part because traditional experimental systems fail to capture the intricate environment where pathogens interact with human lung tissue. The 3D-printed lung could change that by offering a safe, controlled, and replicable model to observe infections and test drugs without relying on animal testing or invasive procedures.

The researchers also highlight the potential for their model to advance the study of genetic and chronic conditions, including cystic fibrosis, where abnormal mucus production and inflammation make drug testing especially challenging. With its customizable structure, the 3D-printed lung allows scientists to introduce patient-specific cells, paving the way for personalized drug screening and precision medicine approaches.

Beyond research applications, the technology holds promise for regenerative medicine. By refining their methods, the team hopes to one day engineer full-scale lung tissue for transplantation or use patient-derived cells to repair damaged organs. Such advancements could help address the global shortage of donor lungs and reduce transplant rejection rates.

The next stage of development will see the team producing more advanced bioprinted models and exposing them to infectious agents and environmental stressors to study their biological responses. These experiments will help validate how well the printed tissue replicates immune function and could lead to new preclinical testing platforms for vaccines, antivirals, and inhaled therapies.

“This work is only the beginning,” said Dahlan. “Once we can accurately replicate lung infections in the lab, we’ll be able to test how specific drugs perform on tissue from different patients. That opens the door to individualized therapies, faster drug discovery, and, eventually, lab-grown replacement tissue. It gives us a direct path to more effective and compassionate lung disease treatment.”

The research exemplifies how collaborative innovation between engineers and biomedical scientists can yield transformative tools for healthcare. By integrating bioprinting technology, advanced imaging, and cellular biology, the USask team has created a living model that not only deepens understanding of lung diseases but also accelerates the translation of laboratory research into real-world clinical solutions.

Ultimately, this 3D lung bioprinting initiative demonstrates how Canada’s growing expertise in biofabrication and infectious disease research is shaping the future of medicine. As the technology matures, it could redefine how the global medical community approaches respiratory health, drug testing, and organ regeneration — bringing the vision of patient-specific, lab-grown lungs one step closer to reality.

The 3D-printed lung model developed at the University of Saskatchewan represents more than a laboratory milestone — it marks a turning point in how scientists and clinicians approach the study and treatment of respiratory diseases. As bioprinting technology matures, researchers are now able to recreate the delicate biological environments that define human organs, allowing them to study disease mechanisms and test treatments in ways that were previously impossible.

At the heart of this shift is the concept of biomimicry — designing living systems that faithfully replicate the structural and functional complexity of natural tissue. In the case of the 3D-printed lung, the research team has succeeded in reproducing the intricate network of airways, extracellular scaffolding, and vascular-like pathways that enable oxygen exchange and immune interactions. Unlike static, two-dimensional cultures that oversimplify the lung’s dynamic microenvironment, this new model introduces a living, three-dimensional context where cells behave as they would in the human body.

This progress has far-reaching implications for infectious disease research, particularly for pathogens like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which cause infections that linger deep within the lung tissue and form difficult-to-treat lesions. Traditional cell cultures have always struggled to simulate the same oxygen gradients and structural complexity found in the lung, making it difficult to evaluate how bacteria respond to treatment. The 3D lung model could provide a realistic testing platform to measure infection patterns, immune cell responses, and drug efficacy under conditions that closely mirror real human physiology.

Beyond tuberculosis, this innovation holds promise for tackling emerging viral diseases — including influenza, RSV, and post-COVID respiratory syndromes. Since the 3D model can be seeded with patient-derived cells, it could be customized to reflect genetic and immunological differences among individuals, offering new opportunities for personalized respiratory therapies. For example, researchers could expose each patient’s lung tissue model to antiviral compounds to determine which treatment delivers the best outcome before administering it clinically.

The integration of bioprinting and personalized medicine could also reshape how new drugs are developed. Pharmaceutical companies currently face long and costly testing processes that rely heavily on animal models, which often fail to predict how human tissues will respond. With bioprinted human lung models, developers can simulate disease progression and test drug interactions in human-like tissue early in the research process, significantly accelerating timelines while reducing ethical concerns around animal use.

As part of their ongoing work, the USask team plans to expose their printed lung tissues to controlled doses of infectious agents, pollutants, and therapeutic compounds to study real-time biological responses. The use of the Canadian Light Source synchrotron gives researchers a unique imaging advantage — they can monitor the internal structure and cellular activity of the bioprinted tissue with exceptional clarity and precision, without harming the sample. This non-destructive imaging approach enables long-term observation of how tissues evolve, repair, or degrade in response to different stimuli.

According to Dr. Nuraina Dahlan of VIDO, these advances are a gateway to more personalized, effective care. “Every patient’s lungs are different,” she explained. “By combining a patient’s own cells with our bioprinted scaffolds, we can model their exact physiology in the lab. That allows us to test how infections develop or how specific drugs perform before treatment even begins.”

Such personalization is crucial for conditions like cystic fibrosis, where the same genetic disorder can manifest differently from one patient to another. By using bioprinted lung tissue derived from individual patients, researchers could identify which antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, or gene therapies yield the strongest and safest response — moving closer to the ideal of precision-based medicine in pulmonary care.

From a materials science perspective, the success of this 3D model is rooted in the team’s choice to use decellularized extracellular matrix (ECM) as the foundation for their bioink. Unlike synthetic polymers, which can fail to provide the correct biological signals, natural ECM offers biochemical cues that promote normal cell adhesion, differentiation, and communication. This balance of mechanical strength and biological authenticity ensures that the tissue behaves more like native lung tissue, enabling realistic cellular functions such as mucus secretion, immune signaling, and oxygen diffusion.

Looking ahead, the researchers envision scaling the technology to produce miniaturized lung arrays, or “lung-on-a-chip” systems, for high-throughput testing of potential treatments. These micro-tissues could serve as a preclinical screening tool, allowing scientists to evaluate hundreds of compounds simultaneously and predict which are most likely to succeed in human trials. Such systems could dramatically reduce research costs and time-to-market for life-saving respiratory therapies.

The same principles driving the creation of bioprinted lungs could also extend to other organ systems, including the heart, liver, and kidney. As 3D bioprinting technology continues to evolve, it’s becoming increasingly feasible to fabricate multi-tissue constructs that simulate the interactions between organs — a key step toward whole-body modeling and organ regeneration.

For regenerative medicine, the implications are even more profound. By refining their printing process and combining it with stem cell technology, scientists could one day generate functional lung grafts for transplantation, made from a patient’s own cells to avoid immune rejection. While still a long-term goal, such developments could revolutionize the field of organ replacement, offering hope to the thousands of patients worldwide who die each year waiting for donor lungs.

The University of Saskatchewan’s progress highlights Canada’s growing leadership in biofabrication and infectious disease innovation. With partnerships spanning the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization, the College of Engineering, and the Canadian Light Source, this multidisciplinary effort showcases how collaboration between life sciences and engineering can yield breakthroughs that advance both research and clinical medicine.

Ultimately, the 3D-printed lung model represents more than a technological achievement — it is a scientific platform for discovery, bringing the medical community one step closer to replicating and understanding the complexity of the human body. By blending biology, engineering, and imaging science, researchers are not only redefining how we study respiratory disease but also laying the groundwork for a future where customized therapies and lab-grown organs could transform the possibilities of modern healthcare.

Powered by Froala Editor